Correspondence / Edimilson de Almeida Pereira and Marina Camargo / Revista Presente

A conversation started in a “cloud”, the following exchange is established around the book Poesia+, by Edimilson de Almeida Pereira. With the premise that the poem is also written by the one who reads it – just as the work of art is as such because someone puts oneself in relation to it –Marina and Edimilson create friction between their research, so that the author and reader weave together developments for the verses as they traverse issues such as geographies, borders and the dissolution of these outlines for the reinvention of other and new territories.

1

Marina: Reading Poesia+ (2019) was (and continues to be, as I keep returning to the book) a profound and rare experience. The encounter with your text refounded in me a notion of country, forming a new geography in places that have once seemed familiar. It is as if the writing caused tremors in the earth, opening the ground to another topography. In times of so much loss, sadness, and anger at seeing a project of destruction in progress, your writing sustains a place of power, where erudition has its feet planted firmly on the ground, where the sounds of chants are an invitation to join in a circle dance.

Edimilson: Over the years I have written several poems in which the country is a theme. There is, in them, the portrait of a place that can be ours or, metaphorically, another territory, where we live our historical experiences. In these poems there is the echo of an acidic poetic voice, which sees the country as a place in ruins. The poems turn against the imposition of borders, probing another, porous country that still needs to be designed.

M: When you answered my message commenting that the reader is co-authoring with the writer, I thought about dance movements, about the gesture of reaching out to another to enter in a circle, sharing worlds through text.

E: I think of poetry as a territory for sharing, even when it expresses itself as a result of the poet’s personal immersion. When the reader reads, they dig themself through the many layers of a poem – some unknown even to the poet himself, feeding into a game of concealment and revelation of meanings, images and perceptions of the world. It makes me think that the poem is always beginning, hand in hand with the unknown.

M: I read poetry as if I were observing a work that has a unique temporal dimension, built through sedimentation and erosion – the approximation of words through slow accumulation, the reduction that leads to synthesis. But in your poems, you can still hear a song, a kind of song that modulates a certain cadence.

E: At this point, I can glimpse what is caused by intervention of chance and what is conscious in my poetry. In the former, the violent and unpredictable shocks of the imaginary generate unexpected meanings; in the latter, I provoke these shocks and try, as far as possible, to direct them to produce a certain meaning that interests me. In both cases there is a cadence that emanates from different cultural rhythms: a traditional sacred chant, the blues, a syncopation of popular songbooks. It’s a wide, uncertain song that spirals into an imagined dance.

M: I think of the text “O que danças?” [What are you dancing to?]. Dance as an encounter between bodies in communion with places: dance marks thought, it is a way of being-in-the-world, as if bodies in space left tracks and were marked by movements, just as poetry emerges from the tracks left by words.

E: This poem was written based on ethnographic data, referring to communities in which one person, wanting to know where another person comes from, asks them “What are you dancing to?” This demonstrates that dance is a fundamental element of the subject and is, in its importance, at the same level of those other questions: “What is your name?”, “Where do you come from?”. Like names and places, dance is also a trail to be followed in case we want to know who we are. The point is that the winds of oblivion strike upon the tracks. Dancing, having a name or a place is not always a guarantee of revelation of who we are. Depending on the circumstances, they are indicators of what we once were and a promise of what we can be.

2

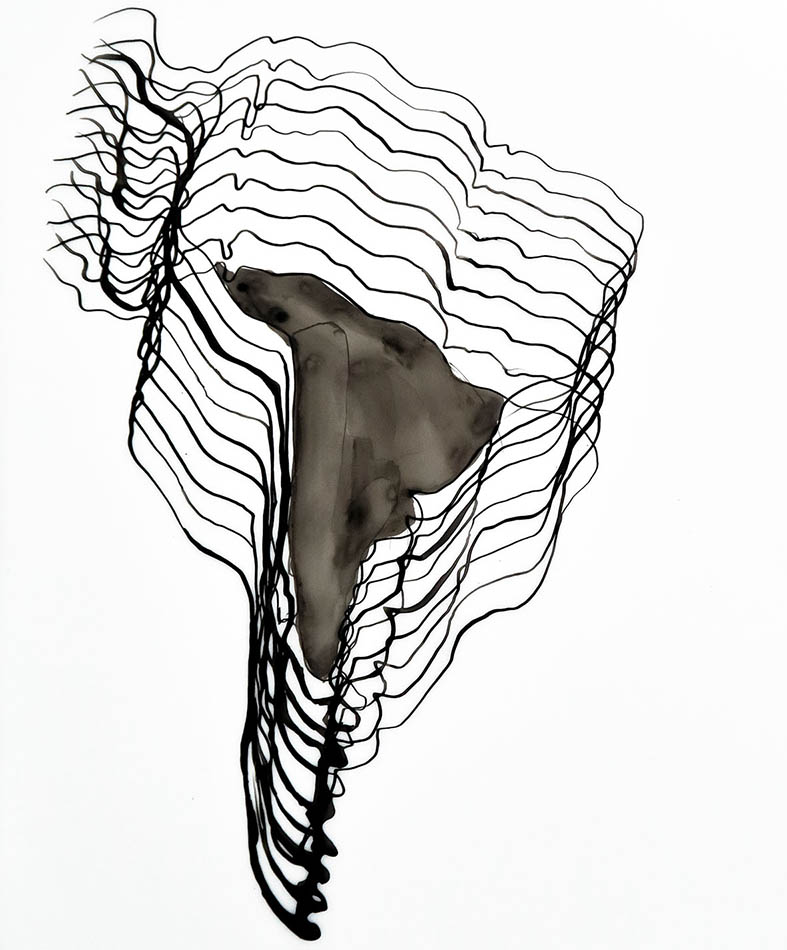

M: Recently, while drawing the political borders of Africa [the drawings are for my piece Songlines, in which the political borders of the continents are placed side by side forming a continuous line, and are then turned into music], I was thinking about the violence that is visible on the map itself, such as the straight lines that divide some countries in Africa – marks of the colonial violence. It’s disturbing to draw these borders, even if it’s just by reproducing a drawing of a map.

E: It is important to question the relationship of maps with the historical moment in which they are drawn. In the case of the neocolonialism that reconfigured African territories, or in the outlines that shape the neighborhoods of our cities, it is possible to see two types of violence: that of invasion and gentrification, and that of the incision on paper or canvas that creates the design of a rationalized world. Charting is, simultaneously, taming and violating a territory. From it, societies decide who is in the center and who is on the sidelines. By analogy, we do something similar to language, even though we have the best intentions. We are charters of meaning.

M: The lines on a map tell stories but do not reconcile us with the past. In Brazil, these borders are not necessarily in our “official” cartography, but they exist as a way of making worlds invisible. What new articulations of thought can create ways of drawing other lines, undoing borders? How can we make a narrative revolution?

E: The violence of the colonization and gentrification processes demands a desperate response, since people suffer, are humiliated and killed over borders. But does art have the resources for a pragmatic answer? Does a poem tear down an electrified fence, does a song grant asylum to a refugee? Objectively, we know they don’t. However, without the myriad of artistic gestures and practices, we would feel less capable of dreaming and, thus, of articulating concrete forms of reaction against the violence of the borders of exclusion.

M: Still on the subject of borders and narratives, there is an issue that haunts me: defining borders involves narrative constructions that alter the relationship of the original populations of the divided regions.In countries that had their borders defined as a result of colonial imposition, the border line that divides entire regions ignores local communities, traditional exchange flows, circulation, etc. These are processes marked by silenced or forgotten disputes, in which the original peoples are systematically oppressed until an apparent calming of the tensions, created by the imposition of physical and symbolic borders.

The process of cultural erasure is implicit in the process of territory demarcation, just as the notion of border extrapolates geographic definitions when socially and historically interiorized.

The question that remains urgent is how to undo borders that are not demarcated on maps, but instead introjected onto narratives?

E: Borders of national territories are, as a rule, the result of specific historical and social moments, when the forces that compose the formation of a State impose the sacrifice of some as a condition for the organization of the social life of others. You have pointed out this process and its inherent contradiction, that is, the affirmation of national history for a group is, as a consequence, cultural restriction or erasure of other groups, in general, the less favored ones. Imposition presides over these chapters of history, revealing a common structure to colonialist or imperialist processes: the use of violence to strengthen a political-administrative centrality in detriment to social coexistences that would bring the human closer to oneself and to other forms of life beyond that of territorial demarcation. In the face of the neoconservative forces that have assaulted democracies in contemporary times, there are no short-term mobilizations capable of making borders more porous. On the contrary, unfortunately walls and physical fences, ideologies and apparatus of repression have reinvigorated old obstacles to the circulation of people and their cultural practices.

3

M: I read your texts and observe that geographies unfold, multiply, explode the map from a lived place, from a place of encounter with the other. Maps that trace influences, places, landscapes, that name people, ancestors, and also note dances, silences. When talking about traces and forgetfulness, I see a deep

inscription build up in the poem “Três tigres” [Three Tigers]:

[1] ESTEBAN MONTEJO E de meus riscos, que ordenam dizendo ser meu espelho? Palavra ilha armadilha, o nunca saber se o escrito é o dito. E, no entanto, floresce literatura furta-cor. Que eu mesmo, de tanto esquecer, talvez, tenha inscrito.

[1] ”ESTEBAN MONTEJO

And of my risks, which they order / saying they are my mirror? Trap island word, the never knowing / if the writing is what is said. And yet iridescent literature flourishes. / That I myself, by forgetting so much, perhaps, have inscribed.”

(Impossible not to think of Esteban Montejo fleeing slave labor on the sugarcane plantations, fighting for Cuba’s independence. The story of one man that encompasses a century).

E: It’s interesting that you talk of “geographies [that] unfold” and “explode the map”. Establishing a physical (territory) and emotional (our feelings) cartography is inherent to our individual and collective history. However, territories and emotions – which can be seen as the geographies of the world and of the being – glide, acquiring forms and meanings that our cartography registers only partially. It is exciting to explore these shifts, still unnamed, although sensed. The polysemy of poetic language is valid for this investigation, since, at the same time that it reveals a landscape (physical or emotional), it indicates that it is fading before our eyes. Poetic language fictionalizes territories, moves and sometimes removes borders. That’s why I don’t see poems as maps for deciphering history or emotions, but as geysers that explode and shuffle shapes, while we try to learn to reconfigure the world.

M: I reread “Diário” [Diary], dedicated to Lima Barreto, and the last stanza accompanies me for days:

[2] “Impossível dormir

como se o mundo não gestasse

a separação do arco-íris”

(p.97).

[2] “Impossible to sleep

as if the world weren’t gestating

the separation of the rainbow”

And also, in “O jogo travessia” [The crossing game] (dedicated to Benjamin Moloise):

[3] O PAÍS

existe um país

mas o rasgam

e as coisas ameaçam

desaparecer

o carvão

não pode sorrir

em podres

insetos

o país é um assustado

gesto de procura

que procuro.

[3] THE COUNTRY

there is a country

but they tear it apart

and things threaten

to vanish

the coal

can’t smile

as rotten

insects

the country is a scared

search gesture

that I search for.

If there are many pasts to be reconstructed, can we think of many possible futures? I think of a different seam, that connects various narratives of silenced pasts towards tomorrows, unfolding from other perspectives. How to sew, in the present, the arch between these other times?

E: Although the materiality of the past is already given, this does not mean that we cannot recover new meanings among its cultural layers. I know it’s a challenge to say this because, in general, you dig into the past to extract models that fuel conservatism. However, that is only one side of the coin. The other side presupposes learning, from the past, the realignment of values and practices that brought us to the present as restless subjects imagining futures. Knowing the reason behind happenings and the choices we make implies taking on responsibilities towards the society we want to build; it implies taking an interest in stories that are not our own and confronting the obscurantist forces that threaten freedom of thought.

(…)

[4] UM HOMEM VAI SEM A PERNA

como um navio que, aberto os porões,

aderna.

Sua gramática é esta.

De falta em falta a história se acumula.

Vão porque há quem os espere.

Âncoras.

[4] A MAN GOES WITHOUT A LEG

like a ship that, with open holds,

sways.

This is your grammar.

From wanting to wanting, history accumulates.

They go because there are those who wait for them.

Anchors.

4

M: I think about the approximations (or contaminations) between field research, academia, poetry, prose; between the work as a professor, researcher and artist, an anthropologist and poet. How does the porosity between these fields structure your thoughts and your writing?

E: I have often been asked what relationships can be established between research and creative writing, between the researcher and the poet. This attribute of relating different areas and voices of discourse pertains to subjects from all periods. In the so-called Western modernity, this attribute came to the public scene recognized as a mark of a time when the subject is forced to dissipate into multiple areas of interest. As a result, to act in a performative way, constructing and deconstructing meanings, explicits both our creative potential and our attempt to overcome the anguish of fragmentation. This dilemma, tensioned by an audience increasingly interested in knowing what is behind a work, characterizes us as subjects that are displaced even in that which we create. We are the origin and loss of origin of what we do; we become self-referential and, at the same time, called to action in the most forceful social struggles. Hence the porosity that installs itself as a cultural mode (because it is constructed) of our relations to the various fields of knowledge. Resulting from this are hybrid forms of thought, in process, porous and averse to watertight categorizations. It is in this scenario that I am willing to write. However, I depend on the circulation of everything I’ve written so that the public can apprehend this dislocation between genres and themes, with multiple and tensioned views.

M: When I speak of structures, I think of a root, an organic structure that expands into solid and multiple branches, in constant contact and contagion with a complex environment (somewhat different from the Cartesian logic).

E: I understand your description of this “organic structure that expands into branches’’. Glissant called it not “root” but “rhizome.” If the first is based on an axis, the second is the result of a series of branches that relate to each other and the ecosystem in a continuous process of expansion. Gains and losses are part of this process, allowing it, in terms of philosophical expression, to express itself as a radical thought of foundation-destruction of the world, of criticism and self-criticism, of isolation and dialogue. This rhizomatic view is at the base of my writings. It can be seen in poems such as “Instrução do homem pela poesia em seu rigoroso trabalho” [Man’s Instruction through Poetry in his Rigorous Work] or in an essay such as Entre Orfe(x)u e Exunouveau [Between Orfe(x)u and Exunouveau].

5

[5] CANÍCULA

Lá fora é um jogo de montar, penso, desde que deixei de acreditar na realidade. Refazê-la é um modo de expor o olho do armador e também a condição para que meus pares, defendidos do risco das grandes lutas, me dirijam seus elogios. A certa hora, quem separou o fio da navalha hesita em erguer pontes: amenizam o exílio, mas através delas os violentos atingem nossa consciência. O que me dizem, meus semelhantes? empenhados em secar o oceano. (…) p.361

[5] DOG DAYS

It’s an assembling game out there, I think, since I stopped believing in / reality. Remaking it is a way to expose the riggers’ eye and also the / condition for my peers, shielded from the risk of big fights, to offer me / their praise. At a certain time, those who walked the razor’s edge hesitate / to build bridges: they assuage exile, but through them, the violent / reach our conscience. What say you, my fellow men? / committed to drying out the ocean (…).

M: Like a sort of immaterial archeology, language reveals the layers of time, encounters between peoples, and amalgamations between different languages. Is the Atlantic Ocean a fluid territory from which this immaterial archeology can be reconstructed? How can one remake reality?

E: Very beautiful and appropriate this expression you used, “immaterial archeology,” Marina. Thank you for this gift. The oceans, the swamps, and the fields are fluid territories. People lived and live in them concretely. At the same time, there are nuances of life and history that pervade these territories; to apprehend them, it is necessary to develop non-palpable instruments: immaterial shovels, spatulas, and tweezers that help us see what subsists in the material world in which we live. It is through language I believe that we forge these instruments. The poem “Dog Days,” which you quote, begins precisely from this perception. While developing it, the poetic voice is not concerned with saying what reality is but with pointing out what choices we make while faced with the simultaneous realities that permeate our body and thought.

M: Somehow, a map is drawn of places, people, authors, and also of stories, violence, and bodies that were marked by all these instances. [6] “Rastreio para não trair a palavra do meu tempo.” (O Bicho, p.99)

[6] I track so as not to betray the word of my time.

A trail of traces written by poetry, between devotion and devouring, language sustains this abstract place that unites us. “Mas o texto captura é o rastro / de carros indo, sem os bois. / A poesia comparece / para nomear o mundo” (in “Santo Antônio dos Crioulos”).

[7] But the text captures the trail / of carts moving, without the oxen. / Poetry appears / to name the world.

E: This “trail of traces” that crosses the map questioning its rationality and that drifts to another “abstract place,” I think, is an attempt to understand our experience beyond the pre-established codes. Codes are important because they help us illuminate senses in the dark. However, it is restrictive for us to spend our lives immersed in this luminosity. It is also necessary to see the dark, to be inside it. “Naming the world,” from this perspective, is not being stuck with what has been revealed but being attentive to what is hidden beneath it, in constant risk of devouring what we know. Text and writing are not fixed lines that capture the given reality, they are broken lines that try to draw a world and mend themselves simultaneously. Because of this, the world they unveil is unfinished, the result of the cracks they carry within themselves. Because of this, we will also be challenged to fill – successfully or not – the gaps in our thinking, and in our ways of relating to others.

Revista Presente was conceived by Anna Maria Maiolino e Paulo Miyada

Editor Paloma Durante

Graphic design Vitor Cesar

Layout Julia Pinto

English translation Barbara Wagner Mastrobuono