1. Fractal satellite images, aligned to the circumference of the earth by GPS, seem to make everything that has hitherto formed the art and science of maps superfluous. Perhaps Google will soon have the same effect on cartography as the photo had on painting in the late 19th century. Freed from the task of representing routes and territories, cartography could move into its impressionist phase, becoming above all a formal exercise. Then it would move into a second stage, in which the map would go back to being an instrument, but now concerned with criticism of the figurative reasoning for which it was employed for so long. One thing would lead to another and, sooner or later, we would soon have defenders of the map for its own sake, taking us back to where we started.

Perhaps that metamorphosis is just a matter of time. Maybe it has already happened, but given its cyclical nature, it is impossible to notice. Or perhaps it will never happen, because postmodern as we are, we already understand that no technology is perfect – no matter how representational or automated it may be. We do not expect the GPS, with its built-in errors, to offer a revelation similar to that of the first daguerreotypes. The instrument starts from suppositions: we already know that America is there; we just need to check the best way of crossing it during rush hour.

In these terms, Google Maps serves both as a pretext for marketing [1] and for military errors [2]. It would not be wrong to say that cartography maintains its secular vocation, as a field of economic and political speculation. To a great extent, the map never represented any territory. The map produced territory, placing north at the top, Europe in the middle and England proportionally bigger than it really is. Therefore, the true difference between new and old mapping technologies – cartography before and after the GPS – lies neither in technical accuracy nor in semiotic precepts, but in its rhythm of use and information.

Cartography is living through an Era of Abundance and Waste. There was a time when map-making was a laborious craft, involving years of research, calculation and skill – and even so, it produced no more than an approximation of route, subject to successive revisions. Nowadays, though, it is enough to go out with a cell phone in one’s pocket and, thanks to discrete triangulations of signal, mapping is firm and inevitable. But if the continents have already been discovered and there are no new places to explore, what purpose must we give to this surplus of representation?

2.

There are works by Daniel Escobar that reduce the map – and the tourism-marketing photo – to mere matter. The artist seems to go to advertising ephemera like someone going to a clay pit and extracting material from it. While the cliché is diluted (like mud) its characteristic signs accumulate (like noise), but never reach a fully malleable state of papier-mâché.

The thing that stands out from works like Plano Diretor and Cidades Azuis, for example, is not their particular outlines – which, as a result of the constructive process, I would suggest could be different. Rather than their own forms, what we recognise in these works are vestiges of other forms, which unusually resist homogenisation, in the same way that industrial design persists in Arman’s Accumulations.

As Cidades e o Desejo and Palácio das Esferas, make it even clearer how the work becomes a background for the cartographic cliché, surgically mutilated, to take the role of figure. The facades of paper, with their roots in the pages of tourist guides, reveal them as pedestals: they are the conditions of existence of an impossibly unique Belo Horizonte.

Perto Demais results from a procedure of superimposition, similar to those of Idris Khan, leading us to ask whether the effort of homogenising those icons does not end up denuding them of their very nature as icons. Therefore: when distilled to a vague impression of a place, what remains of the map other than a certain order imposed on the elements of the legend?

3.

A map can also be seen as a diagram or a rhetorical schema, and thus another way of making use of the representation of space is as a method of organisation. Marina Camargo produces her Horizontes Simulados along such lines, creating the underpinnings for the collaborative Open Horizons Project. Her work is therefore the perfect opposite of Daniel Escobar’s: while he produces a transcendental Belo Horizonte from cartographic clichés, she extracts the platonic Horizon itself from its syntax.

Marina Camargo’s works also suggest that cartography, if not natural, is at least a symptom of being in the world. The alignment of heaven and earth does not come from any science, but merely from looking. The calculated projection of the territory (on the plane) results from the inevitable projection of the gaze (over the territory), highlighting reference points and orientation marks.

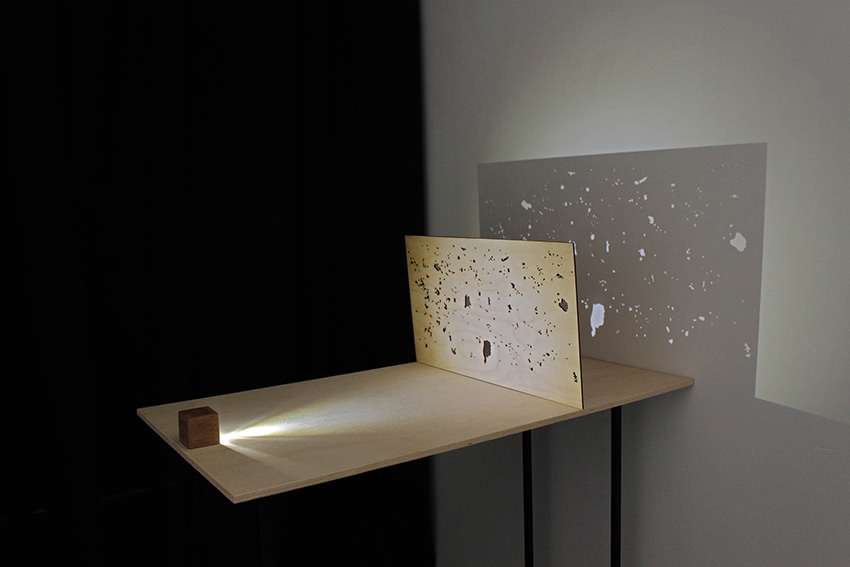

Before being able to chart the oceans, mankind needed to establish celestial coordinates. As in Some Air in Between, the constellations are metaphors projected from the outlines of civilisation. Which is why the ones that have been with us since the Middle Ages have the names of gods and animals, while those that appeared in the 18th century where christened in homage to the clock and the microscope [3].

The interplay of layers in Universo Paralelo illustrates the same paradox: that the sky is in reality illuminated from below, by the imagination, or by the devices of the cities it covers. But this other work also suggests that, taken as reference, the metaphor obstructs the outlines of place – created by the gaze and for the movement, cartography becomes an obstacle for both. As in The End, the orientation of the world is subtly replaced by that of the image, which is not a deceit because we were not expecting any logic from the map anyway, just guidance.

4.

The evocation of the sky over the earth should remind us that the map is, after all, a perspective, but that is never just ours, no matter how much it coincides with our exact position. Every map therefore represents at least two places: the first as an image, which it refers to; and the second as a negative, what it results from. That other place can be from the top of a plateau, where the whole territory can be seen without interruption, or inside a computer, which can accurately calculate the distance from here to the border.

Just as those other places are contained in the map, so are the processes of mapping and their tools, as traces. In their partnerships with Andrei Thomaz, the work of Daniel and Marina unfolds through those processes, as if going into a loop. In Changing Landscapes the image-information, which normally serves as evidence of a specific presence, is itself presented as a cliché, in an amalgamation similar to the one in Perto Demais. Eclipses seems in turn to develop the theme of Universo Paralelo – but here, once the reference point is established, it is one city that cuts across another and then another until the sky of none of them is produced.

In the works in which Andrei operates alone, the map reaches an even more arbitrary level of manipulation. While Marina appropriates cartographic syntax as templates, Andrei reveals them as a game system. In GPS São Paulo, the parameters of orientation that seem to be inevitable contingencies are once again shown to be circumstantial, since even origin and destination are decided at random, and the player-traveller can interrupt the sessions-route at will.

This excess is taken to its ultimate conclusion in the pair of works entitled Horizontal Vibrations and Movement in Squares in which classic patterns of op art are applied to videos purchased from image banks. The most iconic diagram frames the most generic cliché; it seems that now both the rule and the figure have finally succumbed, revealing the particular form of the works themselves.

Here are forms that paradoxically seem to have been excavated from somewhere else, from some archaeological site of the vernacular web;[4] they are forms that seem to contain the warning that historiography is also excessive in this Era, but has still not managed to take us beyond time – and maps, however, varied they may be, will never cover every space.

[1] http://googlesightseeing.com/2007/11/worlds-largest-kfc-logo/

[2] http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2010/11/google-maps-error-blamed-for-nicaraguan-invasion/

[3] http://www.astro.wisc.edu/~dolan/constellations/extra/Lacaille.html

[4] http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/vernacular/

___________________________________________________________

Text originally published in the catalogue of the exhibition “Lugares/Representações“ (2011, FUNARTE, São Paulo – Brasil)