A matter of deletion and other disappearances

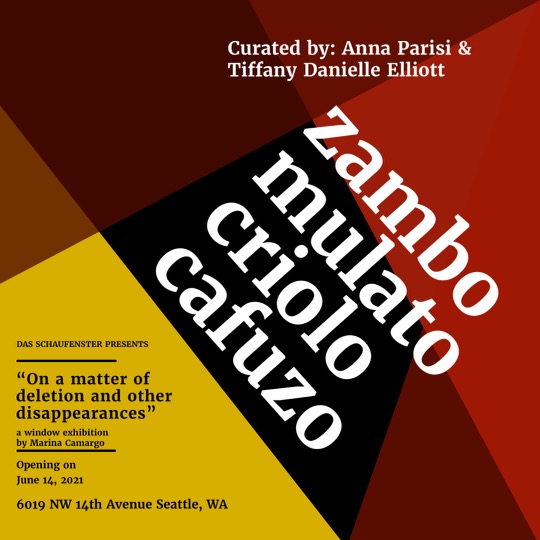

Exhibition at Das Schaufenster (Seattle, USA) curated by Anna Parisi and Tiffany Danielle Elliott.

From June 14 until July 12, 2021.

A matter of deletion and other disappearances

Marina Camargo (2021)

An atlas that I used in school has accompanied me throughout the years. In 2017, reviewing the book, I took advantage of the camera set up on a table in the studio to record an action that seemed urgent at that moment: to erase one of the maps in the atlas, the one that registered the regions where the extractive activity was most developed in Brazil. The map’s title also became the work’s title, Brasil: Extrativismo (Brazil: Extractivism).

* * *

The origins of extractivism in Brazil are linked to the colonization of Latin America and the dawn of capitalism. The extractive activity consists of extracting natural resources and their commercialization as commodities. The mode of exploitation (or mode of appropriation) of nature structures not only an economic model but defines a geopolitical structure by establishing the differentiation between colonized and colonizing regions and the hierarchy between colonial and imperial territories, some being thought of as spaces of depredation and plundering for the use and supply of others. (1)

Since the beginning of its colonization in the 16th century, the history of extraction is linked to Brazil, crossing through time in diverse extraction cycles (of brazilwood, rubber, sugar, mining minerals, etc.). The extractive model deeply marks Brazil’s social, economic, and historical issues, both past and present. It is probably not by chance that the country has been called by the tree’s name extracted to exhaustion until it was practically extinct: the brazilwood. Brazil is a land named after its condition as a supplier of natural resources.

* * *

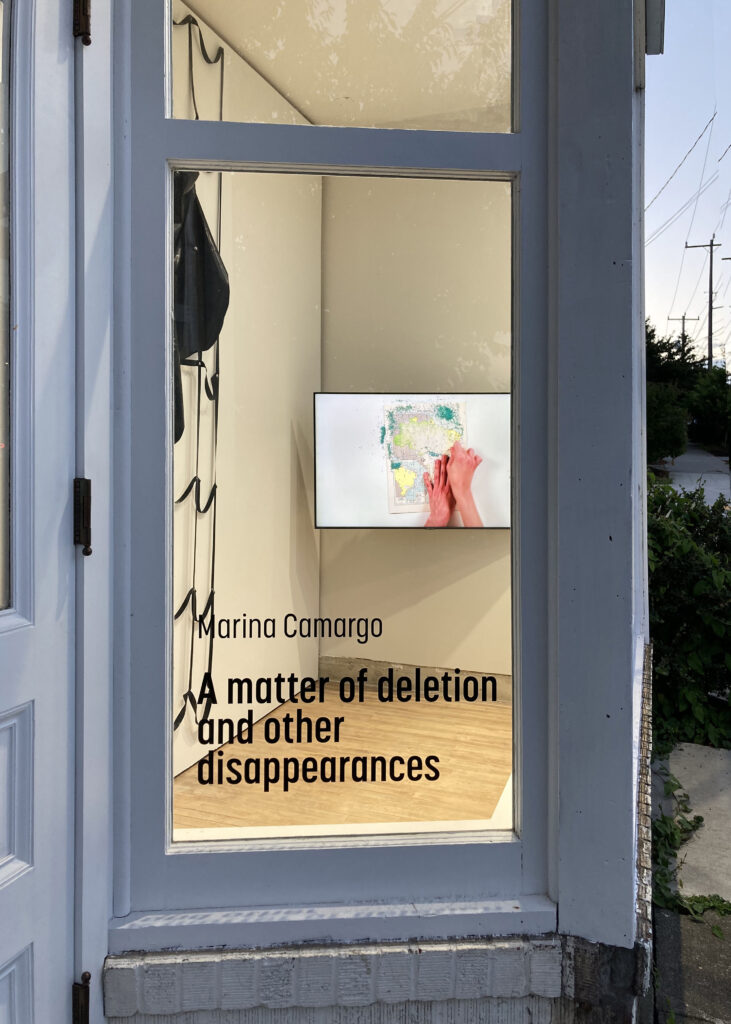

The video Brasil: Extrativismo (2017) records erasing a map in which Brazil is represented through the regions where extraction activities are predominant. In some way erasing the map is to simulate a gesture of the extractive action itself. It is also taken from fury and physical effort, which is a reaction to the rampant and growing deforestation (deforestation increasing exponentially for years, accelerated even more in recent years).

Brasil: Extrativismo was filmed as a continuous take that lasted 10 minutes. The sound of panting and the noise from the streets blend into the image of the map being erased. The slow disappearance of the map reminds us of other erasures as a kind of simulation of the ongoing project of systematic destruction.

Even the rubber that erases the map is part of the history of extractivism in Brazil: latex extraction in the Amazon was central to its economy during specific periods (2). Latex is extracted from the rubber tree (Hevea Brasilienses), the raw material for natural rubber production.

* * *

In América-Latéx (Latex-America, 2020), a map of South America is reproduced in latex, forming a flexible, soft, foldable surface figure. While maps are usually seen as printed drawings (and, today, mainly as digital images), they are transformed into bodies in space into structures that occupy the physical world in the Soft-maps (3) series of works. Once converted into something physical, their corporeal presence also addresses our bodies: one body in front of the other, an encounter that gains an erotic dimension, which contrasts with the nature of maps.

I observe América-Latéx as a disincarnated map of South America, torn out of its abstraction and transformed into a body that is all surface (just like skin) and thus dialogues with our presence.

* * *

I remember learning geography with this school atlas – the same book that, decades later, I would erase, cut out, and redraw. Today, it is an obsolete atlas. The maps, even when outdated, are fragmented records of a time; they expose structures and thoughts in force in specific times and cultures. Based on these records, I build other narratives about places and spaces: destroying to create, covering to make visible, erasing to draw.

———————-

(1) Svampa, Maristella. “Neo-Extractivism In Latin America: Socio-environmental Conflicts, the Territorial Turn, and New Political Narratives.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. P.6

(2) The first Rubber Cycle in Brazil corresponds to the decades between 1890 and 1920.

(3) Soft-maps are works I create using flexible and soft materials, such as rubber, latex, synthetic leather, etc. Beyond the abstraction of traditional map representations, I perceive my research expanding beyond drawings and dealing with a sculptural dimension.